The Pandemic

On top of this it now appears that this convergence might have been coerced into a revolution, and it might have commenced in March of 2020. Like the rest of the world, the Pandemic mantra became stay away, or at least stay apart. As this book is being written the ebb and flow of the virus and the mandates that that brings is accelerating what would most likely have come in the future. Except now that change is needed sooner, and that just might bring change in a way that, in another universe with no pandemic, would have occurred differently. It already has forced something to happen that most in the industry would have said in 2019 and before could never happen.

The Industries Meeting Place

Traditionally the technical media celebrate their Christmas season in March. The vendors, like our band of companies in the Grass Valley/Nevada City area who sell equipment to the various media, see a quarter to a third of their yearly sales happen at a four-day celebration that takes place every April. Unlike Easter, where the day is determined by the first Sunday that occurs after the first full moon after the vernal equinox, this festival was set by the availability of the palace it is held in and the available spaces at the inns that surrounded it. The kingdom over the years has grown huge. Today those lodging spaces number over 150,000.

The Vegas Strip

Like Mecca itself, this desert locale is a 'must' destination for many. In good years well over 100,000 make the journey. They come from over 160 countries to see the wares offered by over 1600 exhibitors like the folks from Grass Valley. Many attendees come planning to spend much treasure for the goods found there. Often over $20 billion is committed to obtaining the products and solutions on display.

Las Vegas Convention Center

To many outside this fraternity who might happen into this two million square foot bazaar, their first impression might be that of a gigantic house of mirrors. The cacophony of sounds, displays, and crowds will at first overwhelm the senses. The first day of the celebration will indeed be a crush of humanity crowding the aisles between the booths where vendors entice you into their dens. Some booths are large, over 20,000 square feet. These represent the goliaths in the game. Each are setup and cared for by a few hundred people. The middle weights take up a few thousand square feet each and usually deploy a platoon size ensemble of sales and technical folks. The small, want-to-be's, the ones occupied by a husband and wife, and maybe extended family, friends, and hangers-on, generally take up a 150-Sq ft footprint. These smaller booths are off the main drag and towards the fringe areas of the gathering. Our band of vendors from Grass Valley are found in all three of these groups most years.

The crush on the first day would subside each of the remaining three days, with a temperature drop in the enclosed parts of the gathering often dropping over 15 degrees by day four as the overwhelming crowd on day one became slightly sparser each day. Day one would be mainly for gawking at what new technical wonders are on display. By the third and fourth days the tire kickers give way to serious buyers who want to nail down deals. Sellers anxious to brag about having a good "show" as the gathering is called, buckle down to close as many sales as possible, and at the same time try not to give away the store.

The convention has been held solely in Las Vegas since 1991. It has about 1800 exhibitors, and over 200 lectures, panel discussions and workshops. When the economy is good over 120,000 attend.

Farnsworth

Like the Farnsworth Air Show, where airframe and engine manufacturers of commercial and military aircraft show off their latest high-tech wonders to an astonished crowd, the same is done at this gathering. While generally not as big, fast, and noisy as what the air show outside London sees, the trinkets, tools, software, and plain old 'big iron' on display and often grandly demonstrated, can mesmerize those in attendance as much as a take-off or flyby of the newest and hottest craft above Farnsworth. The chief products offered by the vendors in the desert will be used by their buyers to inform, entice, entertain, and sometimes enrage the customer's customers, the television and movie viewer.The Convention Itself

Welcome to the National Association of Broadcasters Convention. People who attend it refer to it simply as NAB, or the show. Held for the first time in 1923 in New York City by a radio industry still in its infancy, it bounced around to a dozen different cities over the years until it finally settled in Las Vegas in the early 90s. It is held at the Las Vegas Convention Center, about a half mile off the northern end of the strip. The overall footprint of the center is 4,000,000 square feet.

The show is so large that the largest of the vendors, names everybody knows, Sony, Panasonic, Adobe, Apple, Microsoft, plus other significant vendors that outsiders will not know, such as Grass Valley, Telestream, Black Magic, AJA, start planning for the convention months in advance. Sony's booth is so large, at 26,000 square feet it is usually the largest, that they start planning months in advance and often show up in the cavernous center a couple weeks in advance to start assembling their booth. It is not unusual for Sony to ship 40 trailers full of equipment to Vegas. Their crews are often the first on site. As is usually the case, the convention center does not pay to cool or heat the massive open spaces until right before the attendees arrive, and not so much for the vendors. Generally large portable air conditioning units are spaced around each vendor's booth area to make setup bearable. But there was a year in the 90s where it snowed in Vegas during April setup, and AC units were replaced with heaters.

NAB as an organization is generally a lobbying force for broadcasters. While television and radio stations pay annual dues based on the number of stations a company has, from $500 to several thousand dollars a year, the convention generates a large percentage of the revenue used to fund their operations. Equipment vendors can be associate members of NAB where they pay based on revenue. Mom and pop startups pay $750, while companies like Sony pay $3,500. But as a vendor you do not stop paying there. While the convention center itself charges $0.35 per square foot per day, NAB astronomically marks that up to $49 per square foot (for all four days) for members and $54 for nonmembers. Now that does include basic booth amenities as a booth backdrop, and half height space partitions, a table and a couple chairs. From there booth costs, depending on size and amenities can go up exponentially. 10 by 20 sized booths can hit $20K quickly. Need electrical or other help assembling the booth? That is easily over $100/hour per laborer. Also, if you can't carry it in or wheel it in on an extremely small hand truck, you will have to use union labor and pay a drayage fee for them to get it from the outside of the center to your booth.

The point is that the show is important to companies that sell equipment to broadcasters, but it is also a substantial investment. As was already mentioned, a large part of the attendees are not your typical radio and television broadcast types anymore, as the cinema folks have essentially eradicated the use of film, and now use many of the tools traditional TV production folks use, often in ways foreign to an old-time TV engineer. Today NAB not only bills itself as the voice for the nation's radio and television broadcasters, but the largest show for media, entertainment, and technology. "Where Content Comes to Life" is their recent tag line. They now cast quite a large net.

At the beginning of 2020, the companies in Grass Valley also were planning to introduce their latest and greatest gadgets at that year's show. Some were working on physical products, those you can touch and manipulate, without having a PC intermediate. Today, however, few products do not know how to talk to a computer. A couple companies concentrate on software only products. While stand alone, dedicated products still are churned out by television equipment vendors, many pieces of hardware and software often are bundled into a larger system. So, our merry band of companies were working on items from small boxes that do specific tasks, up to systems that will reside at the enterprise level at a client's facility and help run their business.

Because the industry's Christmas starts on a hard date in sin city, in 2020 it was April 19th, and so much of the money available from customers is offered up then, new competitive products must make it to that show. Invariably, the new product's goals and specs will not have been passed off to the engineers, who are to turn concepts into reality, until the show is much closer than the designers would have liked.

As is often the case some products go to the show and are in reality only partially operational, and through some technical wizardry are made to appear fully capable of their intended purpose. It is like the old film adage, "we'll fix it in post." In this case they will come back from the show make it fully functional on its own, and then figure out how to build and ship it. Yes, there are products, in almost every industry, where you can build and make one work, but cannot churn them out on a profitable basis. A couple of decades ago a company in the industry developed an editing operator interface. This was a time when editors were not just applications on a computer, but often filled a room. The newly developed editing operator control was not only a technological achievement for its day, but it was also aesthetically appealing. It was something Steve Jobs would have liked. The only problem was the power it consumed equaled what an entire household used. Beautiful but un-shippable.

With the engineers toiling away, marketing and sales departments are conceiving campaigns to convince the technical and production types in the TV industry why they will need their latest widgets. Others, spread out across various departments in these companies, none of the companies in the Grass Valley area have greater than 200 people based in the area, are worried about the logistics of getting the necessary pieces and parts to the show, and ensuring that the booth is completed, and housing and travel arrangements are made for all traveling out to NAB.

The Unthinkable No More

While the engineers were looking inward towards meeting their delivery goals, the people that were looking towards Vegas saw conflicting and troubling developments. On a mild Monday morning in the second week of March 2020, sales teams at our companies were coming to face the reality that the unheard of might happen. At the end of January, the state our companies are in, California, had confirmed its first corona virus case. By February travel bans were being enacted between countries. California declared a state of emergency. Other states soon followed. Before that week was out, total worldwide corona cases hit 100,000, with confirmed cases in 90 countries. Worldwide deaths stood at 3,400. That week saw schools in half the states intent on closing.Then for our band getting ready for NAB, lightning struck. The NAB did the unthinkable. On Wednesday March 11th, NAB pulled the plug and canceled the show, an unconceivable move up until then. The gathering place, or bazaar where so much of the industries commerce was conducted was not going to happen that year. Up to a third of the industries equipment and services are purchased during the show. This held true for the folks in the Grass Valley area also.

Empty baggage claim - Empty Casino, same day

It became a "no brainer" as they say. On the 17th the governor of Nevada ordered all non-essential businesses closed. That included casinos, and much more importantly, hotels. Guests had to be out by the 19th. Airlines curtailed flights that week by 90%. The few in the air had few passengers, and mostly carried cargo in the bays where luggage should have been. Soon some airlines were packing packages into seats in the quest for any revenue. With approximately half of NAB attendees coming from countries outside the United States, most with travel bans from them to just about everywhere, and few airline flights to transport the ones that could still fly to Vegas, the final straw was if they got there, they would not have anywhere to stay. End of story.

Like all industries, the pandemic affected the television industry profoundly. Why this is relevant to more than just the people in the industry, is the fact that most looked to television news outlets for information, and over the coming weeks as a source of entertainment as "shelter in place" orders took effect.

Television news immediately faced the challenge of covering the corona virus pandemic while grappling with the guidelines imposed to contain that crisis. Unlike scripted TV programs and entertainment talk shows which halted production in response to the crisis, news operations needed to stay on the air to disseminate information while also trying to keep the COVID-19 outbreak from spreading. "We are committed to continuing our broadcasts and serving the public without compromising the safety of our employees," CBS News President Susan Zirinsky wrote in a memo sent to employees at the time. The virus spread in New York and hit the CBS Network Broadcast Center exceptionally hard, and they essentially shut the place down and ran the network from remote locations. Their owned and operated station in New York took on much of the network operations.

For a while, several news organizations played a shell game. If a New York studio had to be closed to be cleaned and sanitized, all the networks have control rooms and facilities in Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles they can turn to as an alternative. CBS aired its morning program, normally from New York, out of Washington for a while. Their news division's streaming service CBSN started using facilities at the network's owned TV stations in San Francisco and Boston. NBC News originated some programs from London and Englewood Cliffs, N.J., where financial news service CNBC is based.

In fact the networks stepped up their coverage, including prime-time specials on the virus. One news channel went live 24-hours/daily for a while. Immediately the viewer could see how drastically the pandemic had affected the look and content of a medium that had changed little structurally since it first started broadcasting into American homes in the late 1940s. This, while playing to a near-captive audience, producing high ratings, and competing against few entertainment options outside the home.

Practicing social distancing

No studio audience

Viewers could even see the impact on screen as anchors, correspondents and guests were practicing social distancing. This practice to prevent the spread of the virus was demonstrated on news program sets as co-hosts sat at least six feet apart. The traditional shot of the anchors, sports person, and weather forecaster coming together for a group bumper shot disappeared.

Studio audiences went missing. Late night and comedy show hosts live streamed from their homes doing webcam interviews with guests, while the theaters that housed their shows were shuttered. Stunts from performing from bathtubs to host's kids doing their dad's makeup, to backyard and basement stand ups became normal material.

The virus clamp-down hit in March just as production on pilots and episodes for entertainment shows should have begun, putting 120,000 freelance workers in Hollywood immediately out of work. Network television could not produce anything approaching a new fall season.

As a result of the pause in production, inventory, aka shows, became more valuable. Because of their production model, the traditional network's inventory was pretty bare. The networks even scoured other English-speaking countries for limited series that could be shown without subtitles. So, like everywhere and everyone else, the folks who worked in TV had to immediately find more profound and different ways to do what they did. TV has been highly resistant to structural change, but now it had to change in the way they produce content and the way we watch it.

New Workflows

Like most endeavors, TV production can include a single person working by themselves, or dozens. Our vendors up in Grass Valley were among those who created a lot of the tools that the TV industry uses, and now the industry would look towards them to fabricate new workflows. The term workflow is a fancy way of saying what needs to get done, and in what order, and by whom to produce a show, or deliverable in their vernacular.

The typical newscast, be it a local one in Topeka, or a national one out of New York, all have similar attributes. What generally changes are size: the number of the crew and the amount of equipment involved, and the size of the budget. The national newscast will consume more of everything, including money to pay the higher priced talent. Other than the terminology used between the crew, which varies a bit from one outfit to the next, a person familiar with what goes on in Topeka, would quickly sort out what they saw happening in New York.

The workflow up to March to deliver a newscast to viewers would roughly follow these steps:

The news director and producers would decide what stories they would cover that day based on their resources. Often reporters and others would pitch possible stories. While a local station might have a few reporters and video photographers, the national organization would likely have more. That would include microwave trucks and satellite trucks to produce live shots. Other sources available would be from other news organizations they are affiliated with. Often story ideas would come from local and national newspapers.

News Microwave truck (left) and Satellite Truck

Photographers and reporters would record stories which would be sent back to the station, either by sneaker-net, or transmitted via Internet, microwave, or satellite.

Editors would turn the raw footage into packaged stories, sometimes under the direction of the reporter or even the photographer. Often in smaller market stations, the reporters will edit their own stories. The on-air talent, the anchors, will often be working on a story or two of their own. In smaller operations the talent often is the editor-in-chief of the show, although the show's producer usually has the final say.

Studio and Control Room

The technical and operations folks in charge of cameras, studio lights, graphics, the video, and audio mix, will start to congregate towards the studio and control room about an hour out. Any live shots from the field will start to be setup about this time. During a large newscast it is not unusual for the control room to have eight to ten or more people in it, depending on that news day. The studio can easily have a half dozen or more in it.

Now suddenly, whether you went to work or not depended on several things. Were you really an essential service? Most in broadcasting had that mindset. Historically when weather and other events shutdown all else, people in broadcasting were expected to find their way into work, and the ones already there were expected to stay if needed.

But like all other situations, there were other mitigating factors. Do you really want your staff exposed in close spaces, like control rooms or news trucks? In a few cases unions stepped in and demanded spacing. Many simply got inventive on their own. Reporters started using smartphones and became their own photographer. The selfie became a legitimate production tool.

How guest interviews were handled

Reporter using a selfie stick

Other changes rapidly appeared. Most guests and contributors started appearing from remote locations outside of studios from their homes, some via Skype, many more on Zoom as its use, and stock prize skyrocketed. Broadcast and cable networks put on programs with reduced staff and producers working from home. Soon other people began working from home. The news staff at one cable network working from the studio went from 74, to two. The two were technicians to keep the core facility operational for everyone else who were now using and manipulating it remotely.

Whole television markets were now sending a lone photographer to news events such as a press conference, then sharing the video. Fewer photographers on site meant better social distancing and freeing up the other photographers to chase down more enterprising stories. At the start of the "new normal" viewers were more lenient about production values that may not have been what they were accustomed to.

Working Remotely

Working remotely is not anything new to many in television, as reporters have worked from news vans and hotel rooms for years. The big change is that over the years, television facilities central core has become data centers that can be virtually accessed over the Internet. In some cases, parts of that data center do not actually physically reside on the television facilities property. It is hosted on someone else's servers accessed by the Internet. This is the nebulous "cloud"often referred to, and now, what use to be physically associated by necessity, can now be distributed across multiple locations. Later on in this chapter we will look at that much more closely.

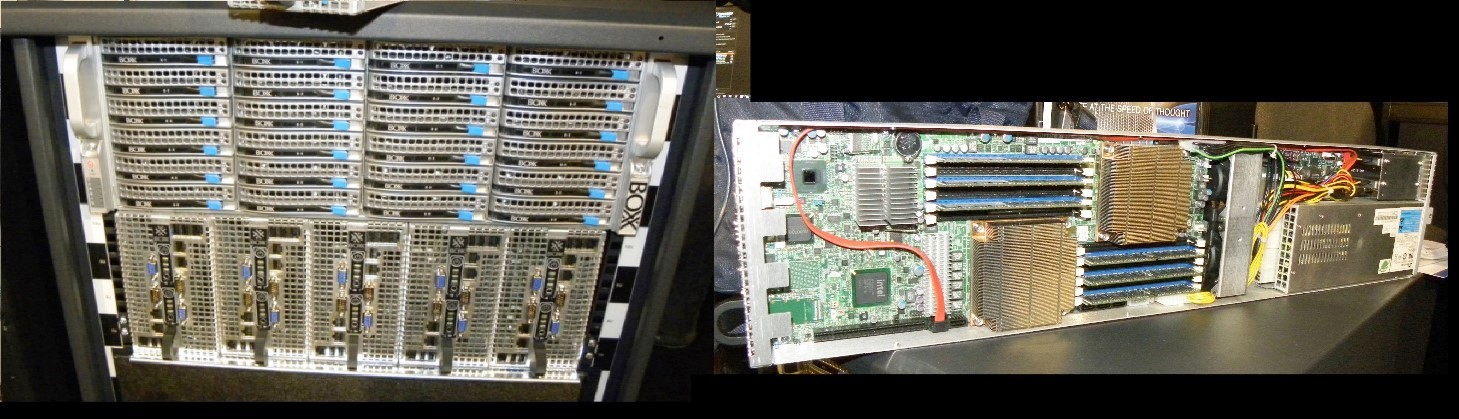

Traditional equipment racks

It used to be that equipment racks in television facilities were filled with specially built equipment. They were designed to do at best a few different things. They took signals in, processed, or modified them, and spit the result out for the next box down the food chain to do its thing. That happened until eventually the signal left the station and was conveyed to your TV. Today, in many cases, equipment residing in racks may look like specialized boxes or equipment, but under their covers, they are computers at heart.

They are not just a piece of equipment that uses a microprocessor as its control system, or brains, but an out-and-out PC, albeit one with some special IO cards, and software. Yes, some do run on Windows and often are found in critical locations. Even the equipment that is still designed to do a specific thing is usually quite comfortable hanging out on a computer network. Bottom line, most equipment installed in equipment racks today, can be controlled remotely.

In the past, a station's workflows were relatively straightforward. People sat at positions dedicated to doing a distinct set of operations, such as a graphics computer, camera control position, video switching or audio mixing positions. These were dedicated machines doing specific functions. Communications being a vital part of any operation with several people interacting at once required intercom stations with multiple channels that could be easily selected from a dedicated panel.

Some of the dedicated operation positions used today

While in the past many control positions had dedicated operator or control panels, today more often than not a control station is a computer, keyboard, video monitor, and mouse, connected via a KVM switch in the system. This setup allows the duties performed by various operator positions to be easily changed based on the demands of a particular show.

With most things now hanging out on a computer network, operators that might sit at a dedicated operating station or control panel can now be decoupled, or "dematerialized" as some have described, from that location or piece of equipment. That is taking the physical association of hardware/software and moving it to a position that could be connected to or from anywhere else. It is simply remote control over a LAN, WAN, or Internet.

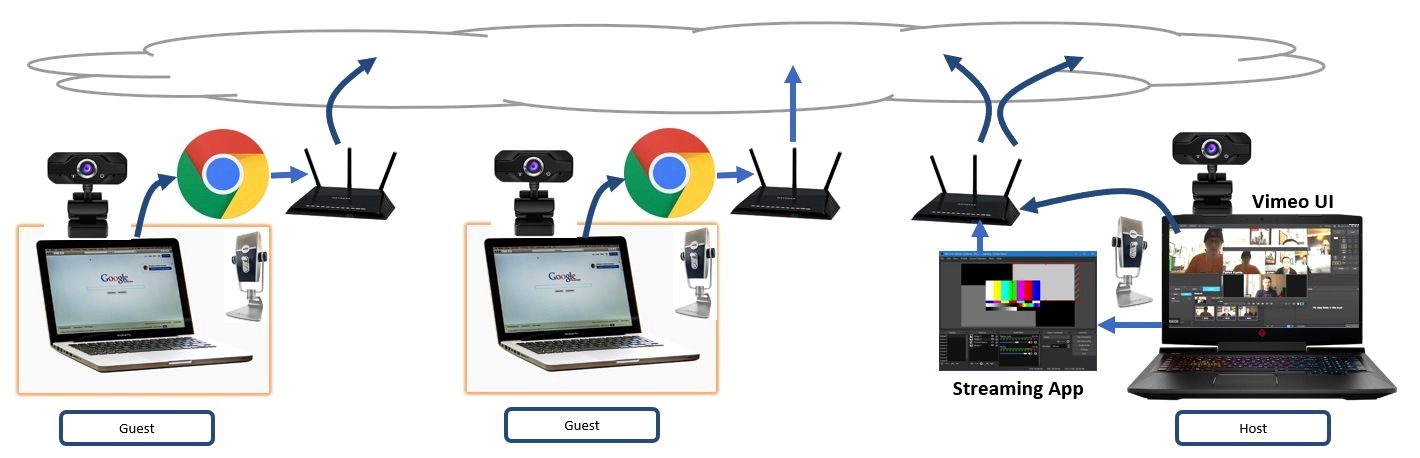

Generic operator stations and topology

Workflows

This means that producers, directors, and operators can control audio mixers, video switchers, and graphics from crew member's homes from around the world. During the pandemic many news reporters, anchors, or other talent had remote controlled cameras in their home that can be panned, tilted, and zoomed by someone across the globe!

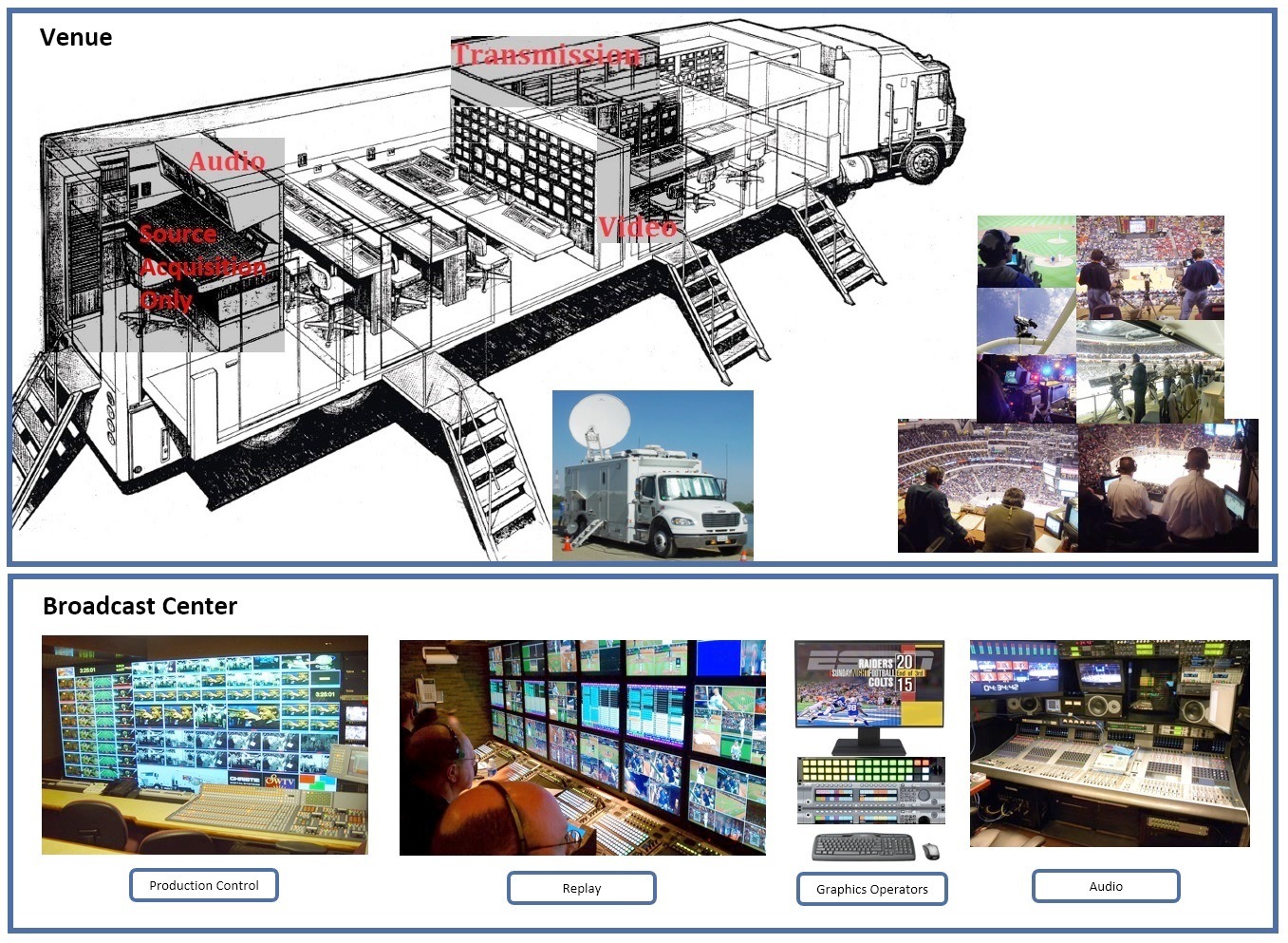

This evolution had been occurring for some time. In fact, when it comes to sports production, as we will see shortly, this had been the goal for almost 20 years, culminating in workflows where many of the folks involved are not on site at the venue, but somewhere else. Only things that are necessary at the venue would be there: cameras, microphones, etc. the "acquisition" tools as they are known. As we will see groups in Grass Valley are instrumental in this development.

The obvious goal is to simplify the logistics, lowering the cost of production. The industry has a fancy acronym for this: REMI (REMote Integration model). This is also referred to as At-Home production. Originally that meant that much of the crew would be at their normal operating position, that is, at their usual place of work, no matter where the game was being done. What was not originally intended was that this evolution would suddenly turn into a revolution where people performed operations from their home, in a risky and accelerated manner.

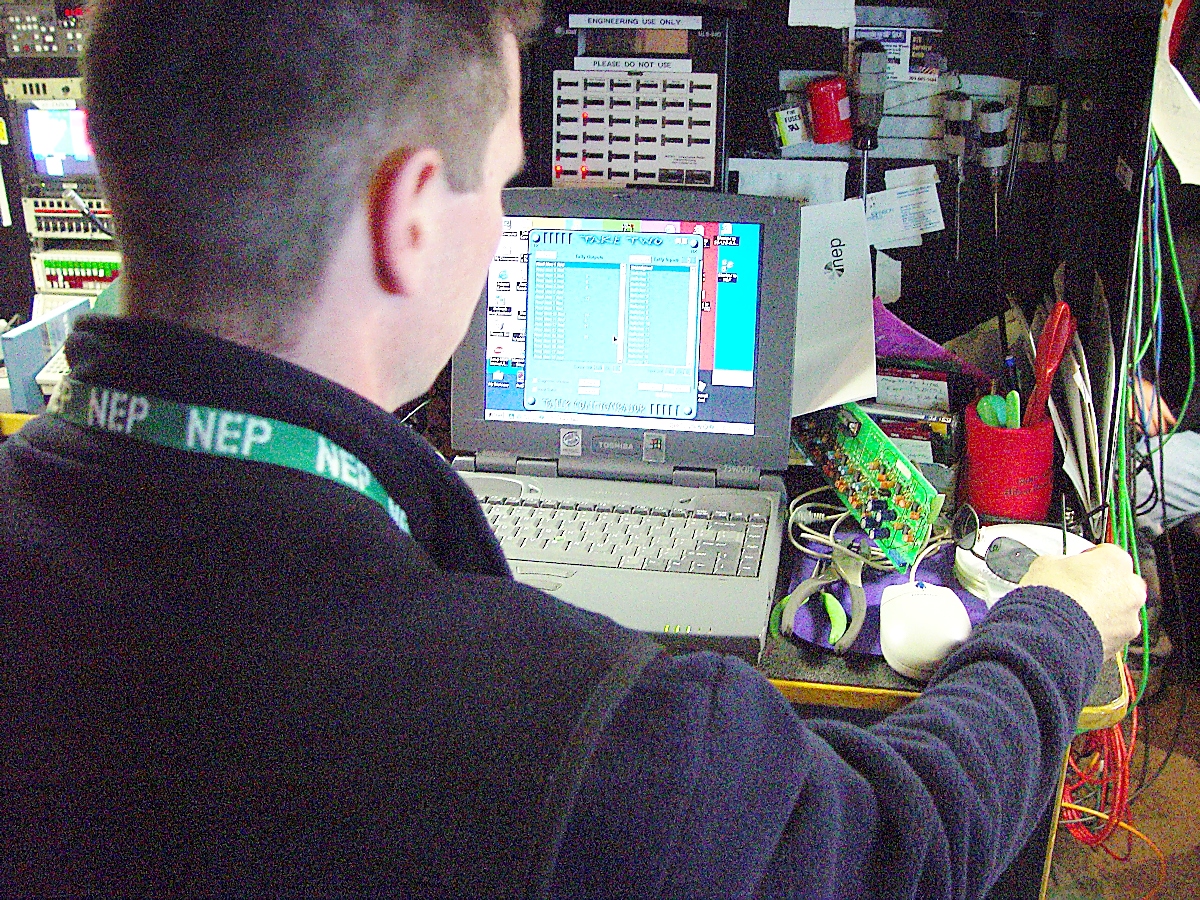

Remote Integration model (REMI)

Whereas in facility operations there use to be broadcast engineers or technicians that cared for and fed the technical center, now the IT person is first among equals. Back in the early days of television the technician often made policy decisions as to what media could air, often citing FCC rules and regulations. Way back then, the FCC tightly regulated what could be in the video payload, not only content and minimal quality, but also how the complete payload was constructed and delivered. Those restrictions have been relaxed as technology has made the viewers display much more forgiving and stable than it was even 30 years ago. Today it is usually the IT person who cites security policy in stopping what the more creative types would like to deliver.

Many facilities strive to keep their business networks separate from their media networks, with a multi-layer firewall between the two, but inadvertently these efforts are thwarted inadvertently by thumb drives and the like.

Years ago, "turnkey" facilities would often be built for a station, that is a systems integrator would build, commission, and test a facility and, when done, turn the keys over to the owner. Today facilities can be built using high powered servers, either your own, or an Internet providers, and laid on top of those servers, services with acronyms such as IaaS, PaaS, and SaaS. In short, the differences are what the station manages in their software stack and what they pay someone else to do. More on these in a bit.

From the station managing their own software running on someone else's server, to lights out, everything is managed by someone else. The facility is simply a client or user. These services mean that even if the users are in their office, they are in effect remoted into their workflow. Better hope nothing affects your connectivity or brings the internet crashing down. Later on in this chapter we will look at the SaaS model much more closely.

As already mentioned during March and April of 2020 the cobbling together of new ways of doing things was centered around cell phones and laptop cameras, often one or the other functioning in dual capacity. They often simply setup Zoom or Skype type calls, or video conferences. In many cases back at the facility a PC that was part of the session simply fed its desktop display out into the facilities video and audio infrastructure and it went to air. A couple of companies in Grass Valley are instrumental in facilitating this.

Reporter working from home

While what is shown here could all be accomplished using Zoom, there is software that is available that allow additional attributes that are usually needed for anything but a very rudimentary TV production.

The biggest hurdle in all this is "comms," communications between crew members. This system was traditionally referred to as intercom. High end ones allow many groups of people to set up their own party lines. Some would need to be on multiple party lines at once. The producer and director might need to talk to multiple groups at once. Many crew members would only need to talk and hear from a single group. These systems, quite simple in the distant past, were now extremely sophisticated. Many now use VoIP.

Specialized software allows separate intercom conversations that others do not hear. Imagine watching a program where you also heard the directors, and producers queuing talent! Or a technical type trying to solve a last minute problem. Most professional production facilities have intercom systems that can host dozens of separate conversations.

This software has host and client versions, where a director, producer, or technical manager can setup and control the various conversations, and a client simply hears the conversations that they need to hear.

This system proved not to be so readily duplicated in this distributed environment, at least not to the elegance that had become expected. Initially multiple Zoom, Skype, or WebEx sessions were set up. Some reverted to a combination of audio and software that allowed instant texting between computers where you could filter out messages not meant for you. Both approaches were hardly optimal. Very soon broadcasters discovered several streaming apps that allowed multiple audio channels on smart phones. Crew members could now use their phones as intercom stations. In short order these apps started being ported to PCs. The loss of comms can be a big deal and grind a production to a halt.

A second half of intercom is what is called IFB. Some say it means Interrupted Feedback, others say Interrupted Foldback. Either way it is program audio that is sent to the talent, minus the talent's own voice, so that they can hear what is going on, such as when the anchors toss the story to them. It is called Interrupted feedback because the producer can interrupt that feed and give the talent cues. The audio mix that the talent should hear does not have their voice included because of processing delays.

Ever try to have a phone conversation when the phone companies echo canceling is not working? It's hard to do. When you see a reporter on location that very deliberately and demonstratively pulls their earpiece out of their ear, it is usually the universal signal that the audio mix contains their voice. The person mixing the audio therefore must set up separate mix for each remote person talking. In many cases today, everyone is at a remote site. The total separate mixes, or stubs as they are known, now has gone up. Life is tougher for the person mixing the audio, especially if they are doing it remotely from the physical audio mixer.

Also tally's; The red lights that come on a camera when it is going to air, or the light in the studio that indicates that the studio mics are "hot." Two of the worse things that can hamper a television production is the loss of intercom, and tally's. So while Zoom is great for normal teleconferencing, it usually will not fly if you need to seamlessly pull off a production using multiple sources and people that needs some "out-of-channel" control.

During the pandemic talent started to receive rudimentary sets. Such as large green displays to allow rolling backgrounds to be inserted behind close-ups of the talent. The ubiquitous bookshelf was growing old as a backdrop. Light kits were often sent to reporters and talent with instructions on how to do basic three-point lighting. This consisted of one light as a spotlight to highlight the face, and second off to the side to fill in shadows, and one as a backlight. The backlight is often overlooked, but it greatly enhances the appearance of some depth with light across the shoulders, so the talent does not look like they are plastered to the backdrop behind them. Next audio processing and equalization equipment was sent, again with instructions and phone support to ensure consistent audio levels, from the talents home.

Multiviewer application

From there things kept being added so that the talent's home studio performed more like a real one. Additional PC's were sent that acted as a teleprompter, which was controlled remotely by an operator. PC's with multi-viewer software showed up. These enabled the display of multiple sources on a single PC screen. This allowed the talent to see the on-air feed, and other sources, such as other people taking part in the program.

Something called PC over IP, or PCoIP, was also employed. It allows for the sharing of a remote desktop with others. This technology is optimized to create little latency, important for live TV. This allowed talent to share content with others, and the central facility to send content to talent.

Besides doing so for the talent, the stations would replicate the multi-viewers video that fed the control room monitors and send it to the various operators so they could see various sources needed for them to perform in sync with others to produce their part of the program. Thus allowing each remote operator, or artist to see the same content as available in the live control rooms at the studios.

Editors were set up a couple ways to work remotely. Either they had local versions of editing software on their PCs, where they would download raw material, edit it down, and upload back their completed story, or they remoted into the stations media asset management system and their local computer acted like a terminal or thin client that manipulated the media remotely.

In the days of video tape, edit lists, that is the list of edit points, would often be created "offline" using copies of the media on less expensive VTRs. Once complete the list would be run automatically on the expensive, high quality VTRs, producing the final to-air copy. Today low-resolution copies of media are often quickly downloaded to an editor's PC, an edit list produced, and sent back to the online system at the station for use with the high resolution media. These low-resolution copies are known as proxies.

Often high-end video servers, which are the heart of these central editing and asset management systems, do not actually compile the selected clips into a new file. They, on the fly, jump between segments in real time orchestrated by the edit list when the story is played back.

Video Servers and file manipulation are a substantial part of what the equipment vendors in Grass Valley area offers. As workflows change, a lot of what evolves and falls out will come from the area.

Sports

But while news is now about the only live TV produced locally, as many stations today look at the rest of their programming as interstitial fill to their newscasts, the other 800 pound gorilla of live television is sports, and it got knocked out for a while. This halted the flow of billions of dollars through sports, among fans, networks, and leagues. NBA playoffs account for $600 million in advertising for Disney-owned ABC, and ESPN, and Warner Media owned Turner. March Madness, broadcast by Turner and CBS, brought in $910 million in ad revenue in 2019.

This caused financial tremors all down the food chain. With NBA's television contracts, those familiar say there is not much latitude for a distributor such as Comcast to say to an ESPN or Turner that it is reducing carriage fees because the NBA playoffs were scrapped. While most cable channels get a few cents per subscriber per month, ESPN charges over a hundred times that. Fallout from lack of content might cause viewers to respond both to the immediate situation and to a potential economic slowdown by dropping their cable subscriptions, accelerating "cord-cutting," the practice of dropping cable, and using only the Internet to stream programming. In TV jargon it is called OTT, or Over-The-Top, which means using the Internet, often provided by a cable company, but not using their cable TV service that rides on the same path.

Losses occurred up and down this food chain. Sports leagues, rights holders, the companies that provide the necessary facilities (very few rights holders, i.e. networks own their own remote technical facilities today), cable and satellite distributors, and the people who crew these events have lost many billions of dollars. Post pandemic, the lowering of costs will be a must.

As mentioned, REMI remote production eliminates the need for large mobile units and crews at the event venue itself, creating a safer environment for production staff by ensuring that social distancing guidelines can easily be met. REMI means broadcasters and leagues can centralize production at their home studios or a dedicated third-party location with minimal crews onsite. The main ingredient to make this approach work are paths with the bandwidth to move all the video and audio captured on site back to the production control rooms.

As shown earlier in the graphic with the large remote production truck, the traditional setup would be typical of a baseball, or basketball game done for a local market. Monday, or Sunday Night Football type events could see a posse of a half dozen trailers of this size to support all that goes into those events, forming a compound that could comprise a dozen or more large trailers for ancillary support and operations when the final tally came in. The Super Bowl: A magnitude larger as it is not a single large event but actually three. There are different trucks for the Pre/Post Game Shows, not to mention the half-time extravaganza that is treated as its own separate show. The Olympics: three or four dozen trucks spread out to cover the various venues. On top of that effort, there are temporary technical centers and studios to tie all the feeds together and offer them to the myriad of networks from around the world airing the games.

Technology is now capable of gathering up all the source signals at a venue; mics, cameras, etc. and transporting them back to be processed for air somewhere else. Instead of dozens of people at the venue, much fewer. Camera robotic technology is now such that most camera shots can be controlled from a far.

Now there will not be a need for all those people and equipment, maybe a single truck the size of the satellite truck might be enough, plus maybe a utility truck to house all the cameras, lighting and other equipment needed outside the truck on site.

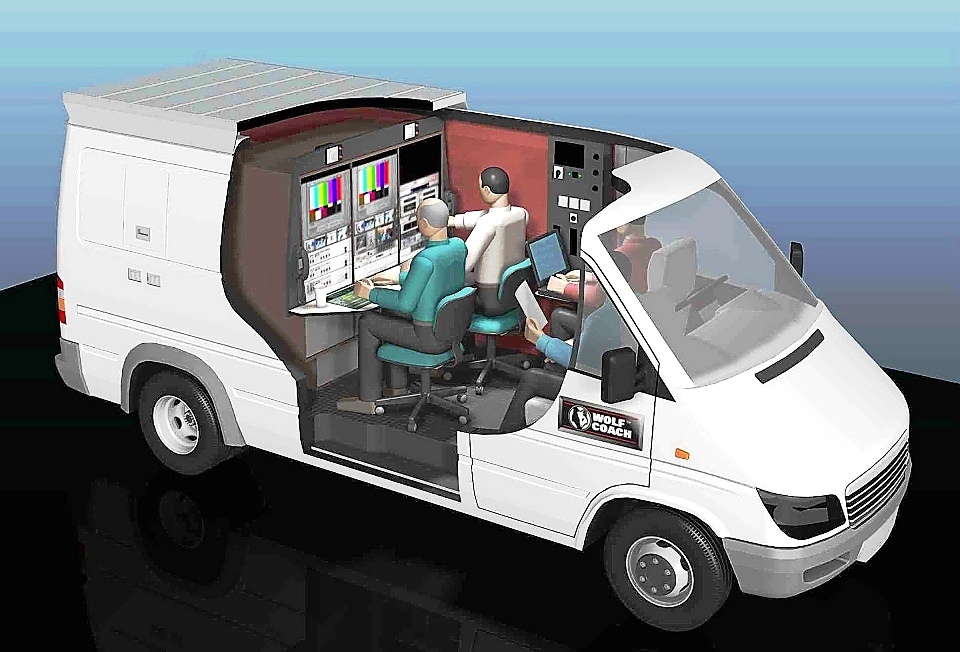

This might be what the truck at the venue looks like

Announcers might also give up their elite travel status on airlines as many games now also have them back at a central facility.

It is estimated that with technology available today, if fully implemented, the cost savings to cover sports production could be 30%. This requires efficient compression, processing, and transmission equipment. All things that technology offers today. Many of these are solutions that are offered by companies in the Grass Valley area.

Not that this is a major consideration when it comes to working out the new production business model, but a side benefit for crew members working these sporting events is enabling production crews to work in a home studio with reduced travel, which can impact the work-life balance of staff, making careers more sustainable. Skilled people who are normally unable or unwilling to travel constantly will now be drawn to working in the sector, widening the availability of good employees. Conversely, there will be less need for the number there were before.

As mentioned, the film and TV industry worldwide experienced a near-total cessation of activity when the pandemic hit, with thousands of largely freelance crews laid off at short notice with little or no financial compensation. A great number of them worked on televising sporting events.

Many production people who work in Hollywood or on sporting events are gig workers by nature. They are "below-the-line" workers, who usually work hourly instead of for a lump sum and are paid less than "above the line" roles like directors, talent, and producers. Like gig workers nationwide, these employees do not receive healthcare from these production companies and do not typically receive paid sick leave. The money can be good, but only if there is work. Hourly rates for what could often be 10-hour shifts ranged from around $130 for production assistants to more than $400, often even $500 for more senior positions.

A typical regional sports network might employ 50-70 people to cover the games they televise. Most of them are freelance. Even the large marquee sports telecasts, like ESPN's Monday Night Football, which was bringing about 250 people to the venue to cover the game, over 200 of them were freelance. With REMI the question is, how many will still be required in the future. Whereas most of the crew working on site at a venue would be dedicated to that one event for one or more days, now a single crew in a central control room, that's potentially a dozen or more people, can now do a multiple events a day.

A constant in remote television production, especially sports, that will not change, is that producers always want more, for less. REMI might be another arrow in the producer's quiver.

But let us look at a cautionary tale that might make some events much more expensive: the 85th NFL draft, which was to take place immediately after NAB at the Bellagio on the Las Vegas Strip in April 2020. Many involved with planning for the NAB were worried about the inevitable overlap between the two events. 600,000 attended the 2019 NFL Draft in Nashville. The hope was that since Nashville had more communities to draw from than Vegas, which in many ways is an island to itself, that many of those counted in Nashville went through the turnstiles more than once. The owner of the newly arrived Las Vegas Raiders, Mark Davis, said he expected the same number of attendees in Vegas.

While Las Vegas has more hotel rooms than any other tourism destination, 86,000 on the strip, 150,000 in total, if the majority were coming from out of the area it is hard to envision those rooms holding three or four to a room. The crew logistics were going to be complicated. But then Vegas shut down. So, the hotel room situation got less complicated, but everything else got much more complicated.

This event had become a major televised event for ESPN, which has its share of major events. The network does over 4000 televised productions on location in a normal year, remotes in industry jargon, and this was a big one, money and prestige wise. Forty years ago, ESPN approached the NFL with a proposal to televise the NFL draft. This was six months after ESPN went on the air in September of 1979. At the time ESPN had no programming from the major sports leagues and only reached 4 million homes. The network filled time with exercise shows, Australian rules football, slow-pitch softball and the like, but the network was an ambitious startup, and no idea was too outrageous.

The NFL owners were dead set against it. "There was absolute unanimity in all the ownership that they did not want this to happen," recalls Jim Steeg, the NFL's VP of special events at the time. "They were afraid that the agents would dominate the draft, so they said no." Pete Rozelle, the commissioner of the NFL placed much importance on the television medium. Rozelle brokered the league's first major TV deals in the '60s. He championed NFL Films and oversaw the franchise it created, and he partnered with television legend Roone Arledge to come up with the wild idea of regular Monday Night Football. So, 10 years after the birth of Monday Night Football, Rozelle was ready to champion another out-of-the-box idea, and he did not care that the owners had just told him no. He gave ESPN the green light to proceed.

Over the years the draft show went from an internal NFL function to draft players, where a bunch of guys talked to potential draftees over the phone, to appointment TV. Today ESPN reaches over 200 million homes. In 2019 nearly 50 million viewers watched.

Roger Goodell

The 2020 NFL Draft was supposed to be one of the most elaborate productions in NFL history with the league ferrying players via boat to a stage on the Bellagio fountain, but that pageantry ended when the event became a "virtual draft" due to the corona-virus pandemic. No Las Vegas, no live audience, and no boats.

Both ESPN and NFL Network went live with the first round on April 23. The ESPN's anchors were at the network's studios in Bristol, Connecticut. Players, coaches, general managers, analysts, and NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell were in their homes. Goodell reportedly announced the first-round draft picks from his basement.

To pull this off ESPN had to coordinate more than 100 camera feeds from nearly 100 different places for the draft. ESPN and NFL Network's production was done using a vast amount of technology. Amazon Web Services hosted hundreds of camera feeds through its cloud system, Verizon helped with connectivity and supplied more than 100 phones for communications, Microsoft worked with several teams to create virtual war rooms and Bose provided more than 130 headphones.

The draft could be a watershed moment in media, said Michelle McKenna, the NFL's chief information officer said at the time. "This might impact the way we traditionally mix user-generated content with traditional media in the future," McKenna told CNN Business. She added that the league sent "tech kits" to those who will be on air during the draft. The kits included multiple phones, a light, a microphone, and a tripod stand. The iPhone production kit for the NFL Draft was sent to players, coaches and GMs, and a handful of owners.

"Typically, in a broadcast situation, you have professionals that are curating and transmitting the programming. We are now having individuals create and transmit their own content," she said. "It's not going to be like having a high paid production camera operator in your living room. It is you. Well, you or your mom." Now you have NFL coaches sitting in their "teched-up" home offices announcing their selections in the draft.

Pushing a lot of the production effort off on the participants might sound like a good deal. But it is more than offset by the fact that the number of individual feeds involved is much higher and spread across the country. This might be the future of many reality shows, this one being the truest example, according to Trey Wingo, ESPN's host for the draft. He also made another poignant observation. "Suddenly the IT guy on your team is the most important member of the entire broadcast."

We might now be in an age where contestants on musical competition shows perform in their living rooms instead of on sound stages with cheering fans and a blizzard of lights and confetti, distributed television production, shows done from nowhere and everywhere.

The new reality, at least for now

Remember that many television production crews have three different sets of employees: people who work for the company that is providing the production facilities, be it fixed or mobile, people who work for the client, be it network or other content producer, rights holder, and the freelance crew. Like all other businesses the media industry implemented a basic and advanced set of guidelines to combat the spread of the virus. The tricky part here is that the client paying for the facility, is also paying for the freelancers. Each client usually has different expectations and requirements, of not only the facilities, but the people they have on salary, and the freelancers they bring in. The production truck or equipment vendor has its own set of expectations for how their equipment is used and cared for.

Typically, guidelines and protocols went like this: Like most other industries anyone who tested positive for COVID-19 would not have been allowed in, or in proximity to studios or mobile Units until at least 3 days have passed since recovery, defined at the time as the resolution of fever without the use of fever-reducing medications and improvement in respiratory symptoms and at least 10 days had passed since symptoms had first appeared, or 21 days had passed since the onset of symptoms.

This led to calls for crews to be quarantined for some period before some shoots, either home or if at a remote site, in a common hotel. Their movement was restricted to the hotel and the venue. Travel to and from the venue was usually provided and monitored. Anyone who developed symptoms consistent with COVID-19 was immediately banned from studios or remote sites and sent home.

In both buildings and mobile units, a label of "authorized personnel" was applied to crew allowed inside or in proximity of various production facilities. Authorized personnel are those who were deemed to have job duties necessary to ensure a successful production. Non-essential personnel, including family members and friends of personnel, tour participants, etc. were not permitted.

Of course, PPE was required. In the case of mobile units, authorized personnel operating inside the mobile unit, had to have PPE on prior to going up the stairs of the Mobile Unit. Even in the wide-open spaces at an outside venue many companies required PPE on at all times. Production equipment was usually mandated to not be handled by anyone not wearing PPE. Many companies treated used PPE as hazardous waste and it had to be disposed of in designated containers.

Most vendors of production facilities, either mobile or fixed provided Plexiglas shields in between operating positions as customarily operators were not seated six feet apart. Client crew members were strongly encouraged to provide their own headsets and microphones. If that equipment had to be provided by the vendor, those expenses were billed back to the client.

Many vendors required everyone entering a facility, again mobile or fixed, to "log" their attendance each workday. This was to ensure that a COVID-19 positive test result could be contact traced. Some automated the logging by displaying a QR Code on each entrance and required the crew to scan the QR code one time daily into a smart phone app to ensure proper reporting. In some locals all employees had to answer health-related screening questions through a tracking system at the start of each workday. Employees who did not pass the screening questions were sent home.

CDC distancing recommendations prompted some areas, such as production truck compartments, audio booths, and other confined spaces to only have one person in it at a time, even if in normal times the space could comfortably host more than one person. In addition, in some situations if a crew member needed to make a request for assistance from an engineering technician, they had to use the intercom, and not walk to the technician and converse in person.

Each crew member was expected to clean thoroughly his/her workspace after each event. Crew members handling any equipment such as cameras, tripods, mics, lights, etc. were required to wipe down all equipment with provided cleaning supplies prior to and after use. Some clients requested professional cleaning services before they would use the facility.

Food and drink were banned from many places where it was allowed before. On many mobile units no luggage was allowed inside the Mobile Unit. Backpacks had to be contained in each person's assigned workspace in the mobile unit.

One of the many potential problems with these scenarios is if someone did test positive, that could take the facility out of service until the space was deemed sanitized. This was not a problem as many fixed facilities were dark, and most mobile units were parked and not in use.

This was the reality for the user side of the production equipment. What about the equipment vendor side of the pandemic equation? Many of the constraints above also applied to our friends in Grass Valley, but they had a few added requirements. Like many other industries the majority of their support functions were provided via on-line support and the majority of the support personnel were provided all the necessary tools to enable secure connectivity in a "work from home" setting so that uninterrupted service could be provided to their customers.

Support calls that required on-site intervention were handled by local personnel, if possible. Where travel restrictions made such service impossible, the customers were generally offered alternate solutions. Often a downed piece of gear was simply exchanged.

To minimize any chance of not being able to supply customers needed replacement hardware, some companies segregated their manufacturing staff from others in the company.

Like the rest of the world the new normal will not be as draconian, but like the travel restrictions enacted in the aftermath of 9/11, more stringent in how we interact in normal life. For quite a while into the future, the flexibility enjoyed before will be somewhat reduced.

But what is certain to continue will be the workflow changes forced upon the industry that make economic sense, especially the REMI model. As we will see, the Grass Valley and Nevada City area will play an important role in pushing that story forward.